Growing up in Ottawa, Mark Lee developed an early interest in radio, thanks largely to his father, who was a radio program director and announcer. Mark would often tag along with his father.

But he also developed an early love for sports — one of his boyhood idols was Roughrider QB Russ Jackson —, and after his playing days were done at Carleton University, he combined both passions, becoming a nationally-known journalist and sports announcer, most notably with Hockey Night in Canada, and as part of the CBC Olympic broadcasting team.

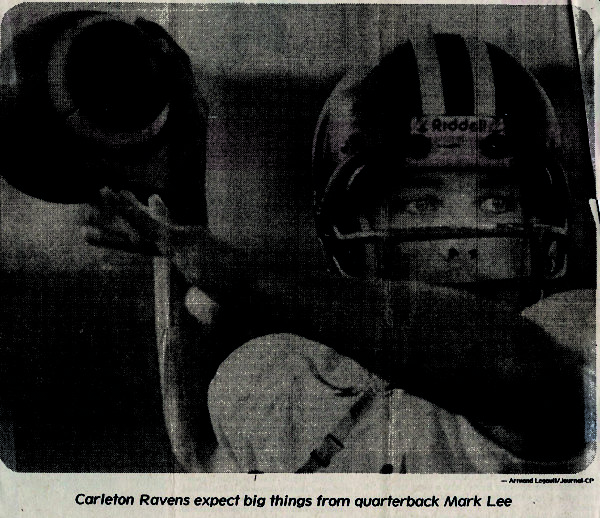

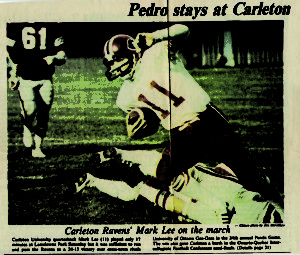

He played hockey in those long-ago Ottawa days — he lived in what was then the small bedroom community of Kanata — as well as football. It was on the gridiron where he made his mark, becoming the starting quarterback for the Carleton Ravens as a freshman in 1975, a position he held for four seasons.

“We played Ottawa U in the yearly Panda Game,” he said. “It was one of the biggest events on the college football calendar, a cross-town rivalry where we’d get 18-20,000 fans out.” As fate would have it, for that first Panda Game the undefeated Ottawa GeeGees were the best team in the country. They were a talent-laden squad; several players went on to play in the CFL.

The game was tied 17-17 in the third quarter before Lee’s team lost 55-22. Ottawa went on to win the Vanier Cup.

But he did get revenge in the last two Panda Games of his career, which Lee’s team won. In his fourth year he had a bad game against McGill, and for the first and only time the coach decided to start the backup. But in the fourth quarter, with about eight minutes to go, the Ravens were losing and the coach put Lee back in.

They won the game. “It was an exciting finish to rally the guys and come back.” The team lost in the semis to Queens that year in double overtime — “a heartbreaker.” Queens went on to win the Vanier Cup.

Lee was there when they re-opened the Rideau Canal for public skating on a yearly basis in the mid-1970s. One thrill on the canal was when he skated with an Ottawa 67s Jr. A player who was billeted just around the corner from him.

Bjorn Skarre was one of the first European players to play in the NHL. “In his one and only year (in Jr. A) he was voted best skater in the OHL. He was an incredible athlete.” But he had his ankle broken in the playoffs in Peterborough that year. “It was a vicious slash.”

Skarre was drafted by the Detroit Red Wings “and in his first year — I listened to it on the radio — Barry Beck of the New York Rangers crushed him on the boards and he never played again. He went back home to Norway.”

But that one magical winter afternoon when they skated together on the canal was never forgotten.

“Back in those days you could bring sticks and pucks onto the canal, and so he’d be 500 metres away and you’d slam the puck up the ice. To be with a kid like that who was new to our country and was such a gifted hockey player and skater, was amazing.”

Entering Carleton’s highly-regarded School of Journalism, he did some part-time radio work on weekends and summers. But his dad, who helped him along the way, made sure he paid his dues. “He was great as a teacher and mentor, and made me realize that nothing is handed to you in life and you have to work hard. I didn’t get paid really well at first, and worked some pretty lousy shifts, but it was a great experience and I got to be around some really talented broadcasters.”

After graduation he took a radio job in Montreal at CFCF (Canada’s First, Canada’s Finest). Within a year he was working radio news for CBC’s national newsroom in Toronto.

In those early years Lee revelled in working alongside some of the giants in broadcasting. “There were all these great announcers from the old days who were really picky about annunciation, inflection and delivery.”

He worked there nearly four years before moving into the national sports department where he did reporting and began covering the Olympics beginning in 1984 (Los Angeles). A year later the Inside Track program began. It was an award-winning CBC Radio program of sports documentaries and in-depth interviews.”I was lucky to get that job and it involved intensive journalistic documentary-making interviews.” Lee won two ACTRA Awards for the Inside Track. The Foster Hewitt Award for Excellence in Sports Broadcasting was presented annually by ACTRA, the Canadian Association of Actors and Broadcasters, to honour outstanding work by Canadian television and radio sportscasters. The award was named after legendary Canadian sportscaster Foster Hewitt.

In 1992 he moved into television when the head of CBC Sports offered him a job in Winnipeg. At the time he and his wife had an 18-month-old child; three days after arriving he was on the air.

“That turned out to be another great opportunity because CBC Manitoba was a hotbed of journalism, winning awards every year for current affairs, and they wanted to treat sports the same way.”

Lee enjoyed doing serious stories — not just sports highlights — about the Blue Bombers or the Jets, etc., and he also got involved with their current affairs department.

“We did a three-part series called ‘The Spirit of the Game,’ which ended up on The National and won a Gemini Award.”

Lee won two Gemini Awards (analagous to the Emmys in the US), first for The Spirit of the Game, 3-part TV documentary on the state of hockey in Canada. His second was in 2011 for best play-by-play.

In 2012 the Gemini Awards and the Genie Awards were replaced by the Canadiian Screen Awards, beginning in 2013.

It was somewhat of a hybrid job. Monday to Friday he was doing supper-hour sports, and every day he had to show up at the morning meeting to explain what kind of story he had that day, and then on the weekends he would fly off and do the network stuff, like football, hockey and some of the Olympic sports.

Five years later he returned to Toronto, doing live-event coverage (play-by-play, hosting) of the CFL and Hockey Night in Canada.

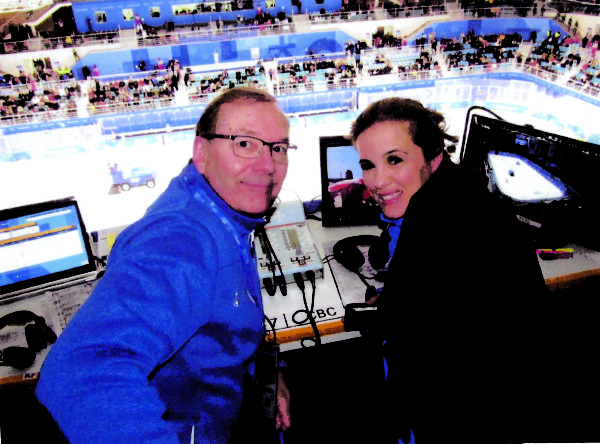

“We lost the CFL rights to TSN in 2007, and at that point I went full-time into Hockey Night, and also did women’s hockey and some of the men’s tournament. His summer sports were volleyball — beach and indoor — and then in 2008 (Bejing) track and field.

All told, he covered 20 Grey Cup games on CBC Radio (4) and CBC TV (16) as host and then as the CFL on CBC play-by-play announcer. He was a host and later play-by-play announcer for HNIC for 16 years until 2014.

The Tokyo Olympics would be his 15th Olympic Games.

At the Olympics he replaced the legendary Don Whitman calling track and field for CBC after his death in 2008 at the age of 71.

Lee was there in 2008 when a young Jamaican named Usain Bolt emerged onto the scene, running to a world record 9.69 over 100 metres, shattering the record held by Canada’s Donovan Bailey of 9.84.

“I felt so fortunate just to have the chance to call that race.”

He looks back now with a sense of wonder. “The tingling that goes through you. You’re in a stadium with 80,000-90,000 people and when the starter calls the sprinters to their blocks, and then it’s ‘On your marks, set.’ And everything is quiet. Nobody is moving. And then these guys come up and the gun goes off and then the lightbulbs flash and the roar is incredible. The energy that comes out of that moment, was just ridiculous. Ten seconds of time. You think about all these athletes who define their careers in 10 seconds. You just marvel at it.”

In 2019 CBC Radio aired a retrospective broadcast called “Back Story” – the story behind Lee’s exclusive 1987 interview with Muhammed Ali and radio documentary on the 3-time heavweight boxing champion who was in decline with Parkinson’s Syndrome.

That interview left a lasting imprint on Lee.

“It was amazing how it all happened,” he said, noting how he caught up to Ali in Miami, where he was promoting a new chocolate chip cookie called ‘The Champ.’

“We had everybody in the documentary — we had Ferdie Pacheco (Ali’s physician), we had Angelo Dundee (trainer), we had George Chuvalo, we had neurologists to talk about Ali, but we didn’t yet have Ali,” he recalled.

“We found out he was going to be at this convention in Miami, so we flew down there hoping to get him, and as fate would have it, the person I sat next to on the airplane was his PR person for the chocolate chip cookie. We struck up a conversation and she helped me get the interview.”

The show was to go on air Monday, with or without an Ali interview. When Lee boarded the plane for Miami, it was the Friday before. Ali’s people had turned Lee’s team down several times.

As Lee got on the plane at Pearson that Friday, there was a lightning storm and the flight was delayed. But, sitting on the tarmac for an hour with Ali’s PR person was a stroke of luck. He explained they were taking a chance on being able to interview Ali for their documentary.

She had been in Toronto for the Toronto Film Festival.

“We really hit it off, and had a great flight,” said Lee. She agreed to help, if at all possible.

“I can’t make any guarantees, but be at the ballroom at the Fountainebleau Hotel at 9 a.m.”

Ali entered the convention hall the next morning dressed in black. Amidst the reporters from Time Magazine and Life Magazine, and the major networks, Ali started handing out literature on Islam.

Ali’s PR person asked Lee to sit next to Ali to get his mind off the brochures, and to try to start up a conversation.

“Champ,” said Lee to the legend. “I just came from George Chuvalo’s place in Toronto last week and he says to say hello.”

“You saw George?” said Ali.

“Yeah, he was still talking about how you never knocked him down at Maple Leaf Gardens.”

Smiling, Ali replied: “George said that?”

Small talk ensued until the ceremony with the mayor began. Lee stayed at the conference all day to try to get his interview. He was told to wait by the house phone after Ali returned to his penthouse.

Thirty minutes later the phone rang.”C’mon up.”

And there was Ali, standing, doing slight-of-hand tricks. Ali moved over to the piano and sat down to play. His fingers soon faltered because of the ill-effects of Parkinson’s. Moments later they sat down for the interview. About 10 minutes into it Lee quoted a neurologist who said Ali stayed too long in the ring and despite his gifts of floating like a butterfly, and rope-adoping, he took too many head shots. “Do you think you stayed too long, and took too many head shots?”

“Turn it off,” said Ali. There was an awkward silence.

“How do you think I’m sounding?”

“You’re sounding great.” He knew he wasn’t. “You’re sounding just fine champ.”

In a flash, Ali clenched his fist and took a shot at Lee, pulling it just short. Lee reflexively flew off his chair and onto the floor.

Looking up at Ali from the floor. he saw Ali flash a huge grin.

”Let’s keep going,” said Ali. Meanwhile, Lee was trying to gain his composure. “I think he wanted to see if I respected him.”

The interview went on for another 40 minutes. “I’m more famous than the Pope and Reagan combined,” Ali said. But eventually he started talking about what he really wanted to do in life, and that was travel to the colleges, where he could speak to the young people. “Boxing just made me famous, but that’s not what I was put on Earth to do. I was put on Earth to be this person that maybe influences people in a good way…”

When all was said and done, Lee rushed back to his room and called his producer. “We have it!”

As of 2020 he’s lived longer in Cambridge than in any other locale, including Ottawa. “I have had some fun with my three children over the years, calling live play-by-play over the loudspeakers of the Waterloo Region elementary school track meets and doing the team introductions at the “Day of Champions” Cambridge Minor Hockey Finals and at the annual Cambridge Roadrunners Girls Hockey Tournaments.”

Once Lee interviewed Cambridge NHLer Scott Walker while doing a HNIC game from Nashville. Walker was out with an injury and he interviewed him during a break in play near the Zamboni. It was the first time the two Cambridge residents — they lived just a few blocks from each other — were meeting, and it happened to be in Nashville. Afterwards, Walker’s Nashville PR guy asked Lee if he could get a HNIC towel, the ones they give for interviews during the intermissions, for Walker. “but they only bring three to each game, and they are guarded like gold,” said Lee. They were only given to players being interviewed between periods, players who were sweating and needed them. Lee was told if they were to give one to Walker, that would mean one of the players being interviewed between periods would not get one. “So we gave it to Walker, and the guy at the end of the game didn’t get one.”

Being a broadcaster also came in handy one day when Olympic runner Carmen Douma was racing in Europe. “We were calling that race for CBC,” said Lee. “Something happened with that broadcast whereby CBC News had to break into our programming in Ontario and Quebec, and so unfortunately, her parents were not able to see her race. I asked one of the technician sot make a video copy of the race.”

Lee had been corresponding with the Douma family for background research and knew where they lived in Hespeler. “I got off the air, we finished the show and I got the tape and drove home to Cambridge and went straight to the Douma house — they had just finished having supper — and I gave them the tape of their daughter’s race which they didn’t get a chance to see.”

Make a donation today, and support the Cambridge Sports Hall of Fame.

Cambridge Centre Mall

425 Hespeler RoadUnit #6, PO Box 444 Cambridge, Ontario N1R 8J6

General inquiries: info@cambridgeshf.com Archives and Nominations: cshf1@live.com

© 2025 All Rights Reserved.