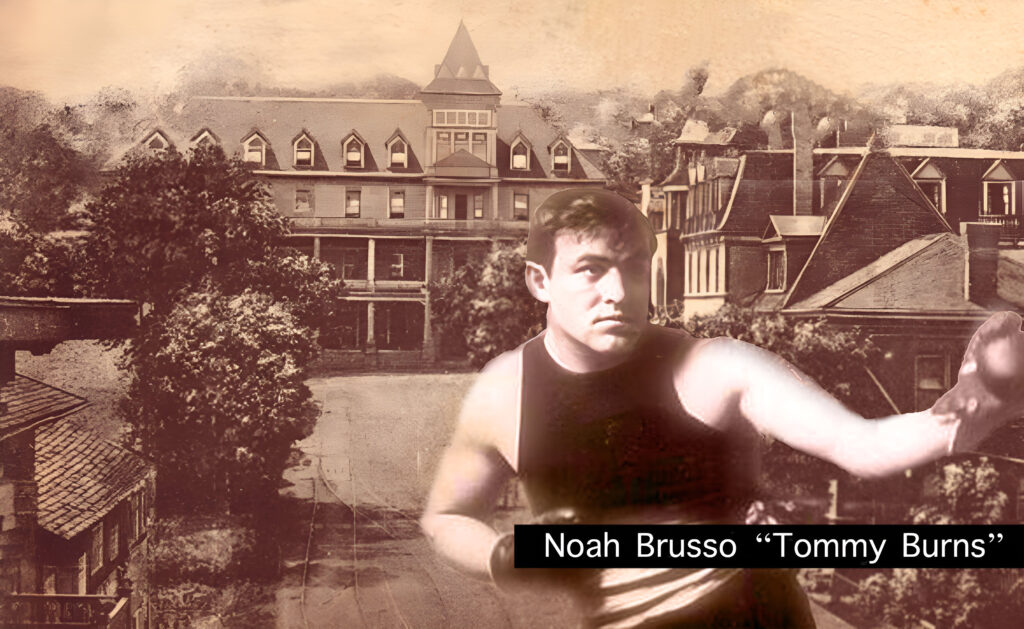

Standing at just 5’7″, Tommy Burns is the shortest heavyweight champion in history. Moreover, only Bob Fitzsimmons weighed less in a world heavyweight title fight than Burns.

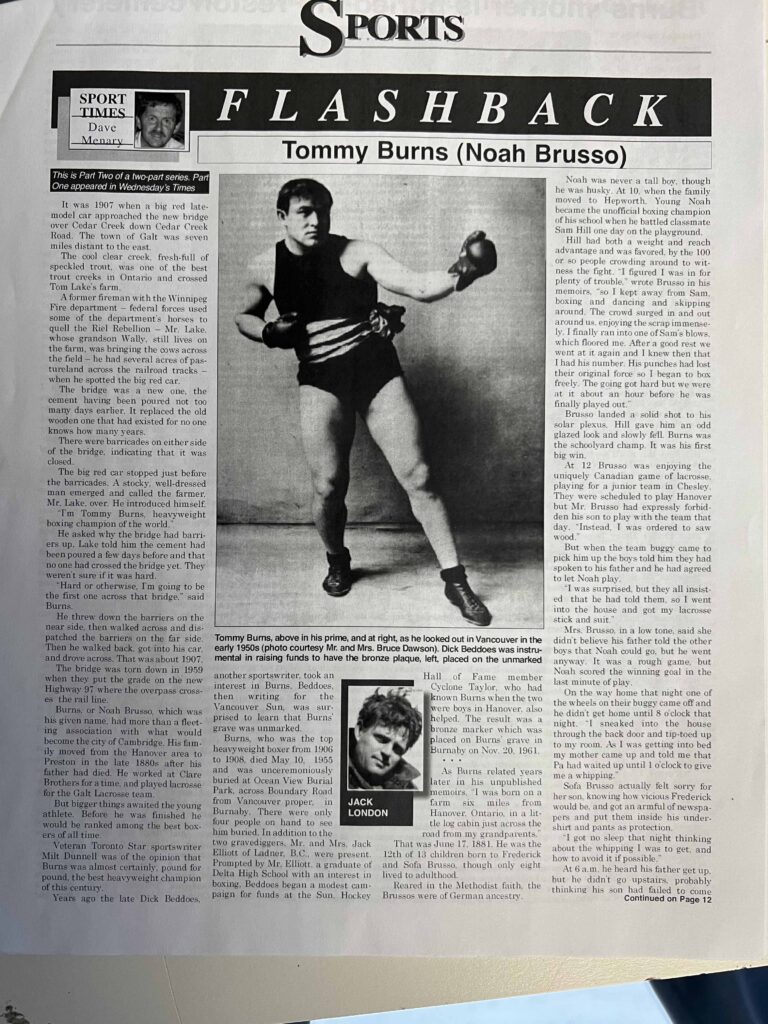

Born to Frederick and Sofa Brusso on June 17, 1881, on a farm six miles from Hanover, Ontario, in a little log cabin just across the road from his grandparents, he was the 12th of 13 children, though only eight lived to adulthood.

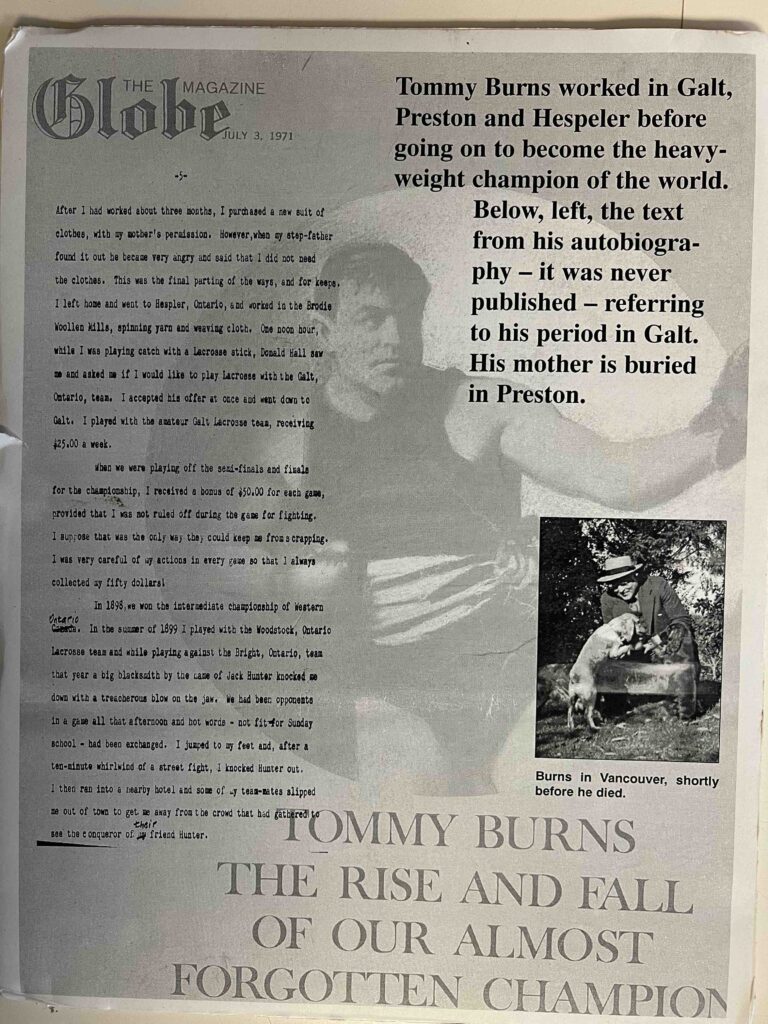

His family moved from the Hanover area to Preston in 1896 after his father had died.

Burns played lacrosse in Hespeler and Galt. He also lived for a time in Hespeler, where he learned to box at a little club led by future postmaster Schultz alongside the western bank of the Speed River.

The late Reporter sportswriter Stan Markarian wrote in a 1980 newspaper story that Burns came first to Hespeler with his widowed mother and his brothers and sisters, where Mrs. Brusso ran a boarding house. That story is in contradiction to other reports, though Noah is known to have lived and worked for a time in Hespeler. It was here, in Hespeler, that Burns began playing soccer with a Hespeler soccer team, according to Markarian. During a game in Drumbo Burns and the village blacksmith fought on the playing field. “Burns lefthooked him in the stomach and followed with a right uppercut to the jaw. The blacksmith crumpled on the ground, his ego deflated and his reputation as the town strong man gone with the wind.”

That playing-field victory brought the attention of Hespeler’s Chris Schultz, who ran an amateur boxing club at the old waterworks building across the road from the Hespeler Furniture Factory. This was where Burns is reported to have first learned the scientific approach to boxing.

Lary Turner, an archivist with the Hespeler Heritage Centre, related that Schultz was a boot and shoe merchant in the small village before becoming village postmaster in 1904. He was active in the community, and his name appeared often in the Hespeler Herald over the years. He continued as postmaster until his death in 1937, operating the post office out of his store at 2 Queen Street East until 1929, when it moved to the new federal Hespeler Post Office building at 74 Queen Street East.

As an interesting aside, the small community didn’t get door-to-door delivery until 1971.

Noah was already a tough competitor on the athletic field, but thanks to Schultz, he learned to strategically channel his power within a boxing ring. He credited Schultz with teaching him the science of boxing. No one realized how far it would take the young athlete.

The question of whether the entire family settled first in Hespeler matters little to his boxing career, of course, though local historians continue to seek clarity.

Winfield Brewster wrote in Hespeler New Hope, C.W, that Burns lived in a house the south side of Queen Street next to Pabst’s Hotel with his mother and a sister. Turner believes that the Brussos lived in Hespeler before settling in Preston. Whether Sofa Brusso and family lived in Hespeler or not, she soon married (1897) a Preston man, Jacob Kuhlman, but Noah and his stepfather didn’t see eye to eye. That’s when Noah left.

“I was unable to fit into the new arrangement and reluctantly went my own way,” wrote Noah in a section of his memoirs that has previously been unpublished.

“I was then learning the moulding trade at Clare’s Foundry in Preston,” he said. The final split for Brusso with his adoptive town came unceremoniously as follows: “After I had worked about three months I purchased a new suit of clothes, with my mother’s permission…When my step-father found it out he became very angry and said that I did not need the clothes. This was the final parting of the ways, and for keeps. I left home (Preston) and went to Hespeler and worked in the Brodie Woollen Mills (where American Standard was later located, along the Speed), spinning and weaving cloth.”

Today many of his relatives are buried in Preston.

”One noon hour, while I was playing catch with a lacrosse stick, Donald Hall saw me and asked if I would like to play lacrosse with the Galt team,” Brusso recalled. ”I accepted his offer and went down to Galt. I played with the amateur Galt Lacrosse team, receiving $25 a week.”

In the playoffs Brusso earned a $50 bonus for each game, “provided I was not ruled off during the game for fighting.” The team won the Western Ontario Intermediate Championship in 1898.

The Brussels, Ontario, native was one of Galt’s early sports heroes. “He was the roughest, toughest, fightingest lacrosse player I ever saw,” said young sportswriter James Herbert Cranston.

Brusso attributed the cardiovascular endurance he got from playing lacrosse as great preparation for his fight career. But he also participated in other sports. “I did considerable ice skating at that time and twice raced against J.K. McCullough, who was the world’s fastest skater.”

Bigger things awaited the young man. Before he was finished he would be ranked among the best boxers of all time. Veteran Toronto Star sportswriter Milt Dunnell said he was almost certainly, pound for pound, the best heavyweight champion of the twentieth century.

Burns ruled the heavyweight division from 1906 to 1908, first winning the heavyweight title on February 23, 1906 at Los Angeles in a 20-round fight against Marvin Hart. Hespeler’s Jack Lawson, a friend of Brusso’s, travelled to California to see the fight. He already had a return ticket to Canada, and some loose change, so he put the rest of his money on Burns to win, at what Brewster called “juicy odds.”

Burns returned to the southern part of Waterloo County—the place he called home—many times after becoming heavyweight champion of the world, and on one such visit to Preston in 1907, he drove a new red car and sported a flashy suit. He also gave a talk to youngsters at the Galt YMCA and showed moving pictures of one of his title fights.

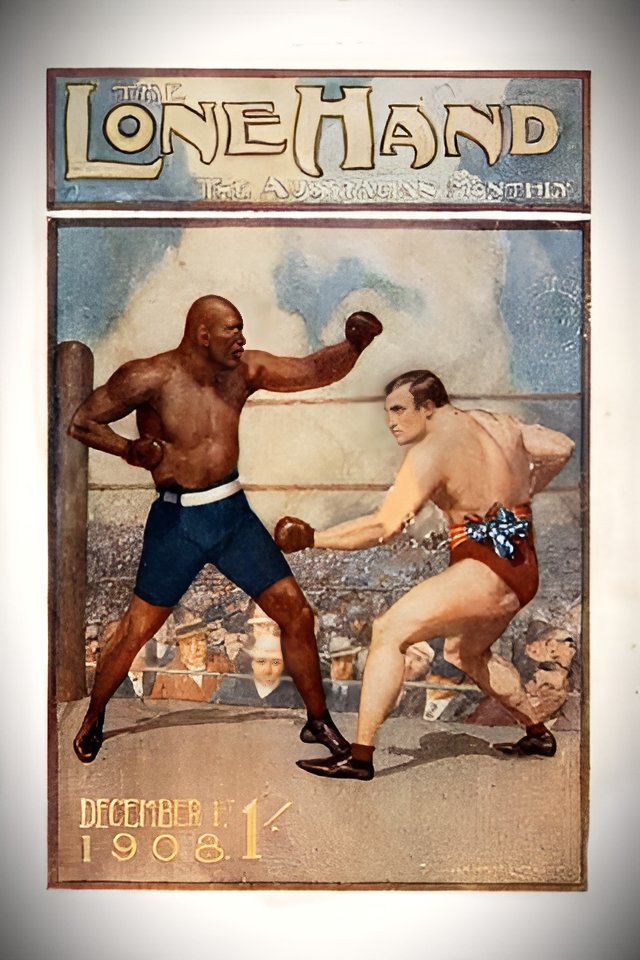

“It will be Johnson next, “ Burns told a local newspaper reporter. They fought in Australia. American writer Jack London, at the height of his fame, was there.

Johnson, the first black fighter to win the heavyweight title, towered over Burns and won the fight. For 14 rounds Burns gamely answered the opening bell, protecting a badly-swolen eye.

All told, Johnson sent Burns to the canvas four times during the contest. In the final round, Burns was knocked down for eight seconds. Police stepped in and ended the fight. It was over. It was Dec. 26, 1908; the first time a black fighter legitimately claimed the world heavyweight boxing title.

Burns died at Vancouver in 1955. At the height of his fame he was feted by hundreds of thousands. At his funeral there were only a handful of people.

Make a donation today, and support the Cambridge Sports Hall of Fame.

Cambridge Centre Mall

425 Hespeler RoadUnit #6, PO Box 444 Cambridge, Ontario N1R 8J6

General inquiries: info@cambridgeshf.com Archives and Nominations: cshf1@live.com

© 2025 All Rights Reserved.