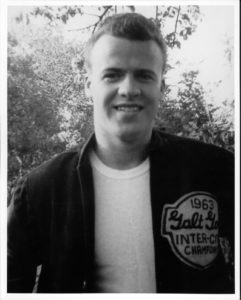

A legend in fastball circles, he was perhaps the most talented player to ever play in the Inter-City Fastball League.

Record sportswriter Tom Conaway always pegged Hopcraft to be one of the premiere pitchers in the country during his heyday in the Inter-City Fastball League.

Teammate Bruce Carswell said Hopcraft was one of the few players he knew who could have made it at the pro level.

“A lot of teams in the U.S. would have paid him good money, but he was never very interested,” said Carswell. “He was more of a home body.”

Another teammate, I-C fastball legend Marty Myska, also ranked Hopcraft among the best he’s ever seen. “He was a franchise player,” said Myska. “He had great pitching ability, but he could also hit with anyone.” In 1967 Myska homered off Dick Hames to give Hopcraft 1-0 win over Hames in the playoffs. Hames is generally regarded as one of the best fastball pitchers in history and would go on to pitch Canada to its first World Championships title in 1972.

Carswell knew Hopcraft well, both as a teammate and close friend. The second baseman played with Hopcraft on the Galt Gores during their six-year run as I-C champs between 1962 and 1967. “He was a people person who liked to have fun.” It was important that the game be fun for Hopcraft. “He put a lot more emphasis on that than he ever did on money.”

His powerful left arm was legendary, but so too was his potent swing at the plate. Several times league MVP, Hopcraft won the batting title in 1965 and his team, the Galt Gores, chalked up some impressive numbers between 1963 and 1968.

Another Inter-City standout from that era, Bob Eccles, recalled how Hopcraft would come over to pitch batting practice as they were getting ready for playdowns in midget and juvenile. Later Hopcraft showed him how to pitch a drop.

Hopcraft, a lefthander, was, by far, the best all-around player in the I-C league. “If you were going to pick one player to build a team around, it was a no-brainer,” said Eccles. “He could hit, field, pitch. There wasn’t anything he couldn’t do. I don’t think I ever heard of him getting tossed out of a game. I never remember him saying anything to an umpire. He was always very gentlemanly. Just a classy sportsman.”

Hopcraft and his talent-laden Gores team drew thousands of fans each summer into their Lincoln Park home field.

In 1965, he threw a perfect game, eliminating the Guelph Co-Ops 3-0. During that game he struck out 17 batters.

Carswell recalled that performance. “I remember him pitching a perfect game against Bob Shaw of Guelph years ago,” he said. “I was a printer and had the box score framed for him.”

The next year he threw a 1-0 game against the Galt Slees to win the final playoff game of the season. He had a batting average of .419. In 2015, he entered the Waterloo Region Hall of Fame.

Ron Reid was Hopcraft’s catcher for years. From the first time he ever caught Hopcraft — a night game in Kitchener, he knew Hopcraft was a rare calibre of player. “I knew he was special,” said Reid. “He was a real team person. If you made an error he’d settle you right down.”

That night Reid saw the young Hopcraft take the field and couldn’t have been more impressed. “I was really impressed with his stuff. I’ve never seen a kid throw a round-house curve like Gerry could.”

But, said Reid, “he had a great curve, drop and fastball, and was very easy to catch. All I had to do was put the glove out.”

Reid said he was on a par with the likes of legendary pitchers Dick Hames and Pete Landers.

“Hames was the type who walked around with the attitude, ‘nobody can beat me.’ But when he came back to the London team after winning the Worlds, Gerry beat him 1-0 (again). It looked good on him.”

In that game, his second 1-0 verdict over Hames, before a Lincoln Park crowd estimated at 2,000, Hopcraft won the game with a home run off Hames.

Hopcraft’s younger brother, Gary, who played on those early Gore teams before playing alongside him on the Cambridge A’s, said Gerry dedicated himself to ball.

“It was his whole life. He used to throw to me in the driveway. I had to know what was coming or he’d have killed me.”

After a four-year battle with cancer, Hopcraft died at age 51. He was survived by his wife Jacqueline and daughter Kelly.

At the funeral, Carswell saw the framed box score from years earlier on his casket and was choked with emotion. “It really broke me up.”

As Conaway noted following Hopcraft’s death, “(he) will long be remembered for more than his ability on the ball diamond.”