June 11, 1926 – Jan. 22, 2008

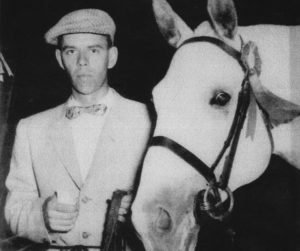

Lorne Siegle, who was born in Hespeler, was a legend in the horse jumping world.

“We couldn’t get enough of watching him and trying to learn by seeing what he did, how he rode, how he trained his horses and how he looked after his horses,” said two-time Olympian Torchy Millar of Siegle.

“He was the person that myself and Ian (Ian Millar was an eight- time Canadian Show Jumping Champion) would always watch,” said Millar. “It was a great learning experience to see him.”

As a youngster in Hespeler, Siegle had strong local roots. His father, who was employed at the Stamp & Enamelled Ware – the family lived on Hungerford Rd. – was a descendant of Abraham Clemens, the earliest Mennonite settler in the Hespeler area.

Lorne was a tall, polite, quiet speaking young man who received his early education at Hespeler Public School. He quickly developed a love of horses and was encouraged in this by George Gretzner, owner of the Hespeler Furniture Factory.

By the time he was 16 he had secured a job riding for a horse dealer from nearby Guelph. Each weekend he would go to Stu Houlding’s stable and put the horses through their paces for potential buyers.

His weekend hobby soon turned into a full-time job maintaining the stable, feeding and grooming the horses and cleaning out the stalls. The work eventually evolved into training horses and riding in jump competitions. It became his life’s work and passion.

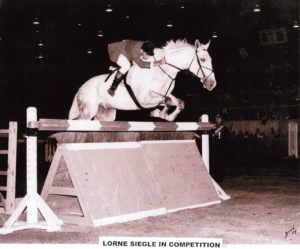

By the 1940s, he was riding for the Cudney family stables and winning his first victories in the show ring. Within a short time he was dominating the competition with breathtaking performances on horses such as War Bond, Kudos, Hell’s a Poppin’, Panama, and Copper King.

Siegle is credited with bringing show jumping into the mainstream. Olympic-designated course designer David Ballard attributed the rise in the prominence of show jumping in Canada to Siegle and other pioneers like him.

“It was a gentleman’s sport before the war and after the war it still had that value to it, but it started to become more of a national sport,” said Ballard. “It grew from people like Siegle.”

His skill as a rider led him to victory at countless horse shows, some of which commanded audiences that numbered in the thousands, but for Siegle, it was all just part of the job.

His rise to prominence as a professional rider happened during the late 1940s, a time when the sport was largely dominated by the military.

During this time, he trained and rode horses with a patience and grace his peers referred to as nothing short of astounding. His stature was such that he was presented with a ribbon by American President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Competing as part of the Canadian Equestrian Team, he became one of the best riders in the world, but because he was a professional rider he was ineligible for the Canadian Olympic Team.

As good as he looked in the saddle, success didn’t always come easily. One day a new horse named Victory Bond threw him 14 times before Siegle managed to break him.

“It happens to all of us,” he said. “If you don’t fall off, you don’t ride. It’s a challenging sport, everyone wants to win. It’s not like racing where there is a big pot at the end. This is just personal, a point of personal pride among the owners”.

Siegle noted that occasionally during a show a horse would gallop at full speed toward an obstacle only to decide at the last minute that it didn’t want to jump, sending Siegle crashing to the ground in front of hundreds of spectators.

Siegle says he kept at it not so much for the money, as in those days a grand prize win at a horse show may have yielded only $1,500, but for the bragging rights.

Wendy Ceccarelli, who helped Siegle look after his Oakville stable, described the riding style Siegle used to bring him so many victories.

“Horses known as jumpers have to clear every jump and there is a time limit involved. Horses known as hunters have to go over the jumps, but they have to look good doing it,” said Ceccarelli.

“What they said about Lorne is that while riding a jumper he not only cleared the jumps fast, but he did it so gracefully it was like he was riding a hunter. That’s why everyone would look at him because he rode so beautifully.”

Siegle would invest a huge amount of time training three-year-old hunters, taking at least a year to train, while a jumper would take even longer.

“It’s all about having a happy horse under you,” said Siegle. “You have to get to know them and they have to get to know you. If the horse is doing well you give it a treat or a pat or something.”

This approach to riding would serve Siegle well as he continued to achieve victories in horse shows, even going on to compete with the Canadian Equestrian Team in Washington and New York City.

In 1960, when he opened his own stable in Oakville, he retired from competitive riding. He would still give guidance to young riders though.

“They’ve got to have the want, they’ve got to love horses,” he said. “They need to watch the riders who are riding now and just keep working at it. A lot of practice, a lot of hours in the saddle and a lot of common sense,” said Siegle. “You can be afraid, but you’ve got to overcome those fears and keep going.”

Memories of his deeds lived on long after his competitive career was done. Riders like Siegle and the horses they rode still waft through the show jumping world. Such is the case with the big old indoor horse arena at 950 Amherst Street in Buffalo.

Every year, as preparations peak for the annual Buffalo International Horse Show, memories of the great horses, riders and performances of the past seem to materialize out of the trophy cases, picture frames and scrapbooks that dot the offices and lounges at the facility. Siegle and Doug Cudney are pictured there, as are Jim Elder, Jim Day and Moffatt Dunlap, five members of the Canadian national team who competed in the 1966 show. And there, too, is the legendary Ian Millar, who competed a decade later when he competed with Rodney Jenkins. The two were among the best known show jump riders in the world.

When, near the end of his life, he was inducted into Jump Canada’s Hall of Fame, several legends paid tribute to the man who had paved their way. Praising Siegle was Jim Elder, seven-time Canadian Olympian, as well as Torchy Millar, and Ian Millar. They each said they learned to ride by studying and emulating Siegle’s style.

By then Siegle was in his eighties. The ceremony, which also honoured eight others including the 1980 Olympic gold medal team featuring Ian Millar, was held on Sunday, November 4, 2007, at the Royal York Hotel in Toronto.

Said Siegle: ”It’s a huge honour for me. To me those things were just part of an ordinary day’s work.”

Lorne Siegle died January 22, 2008.