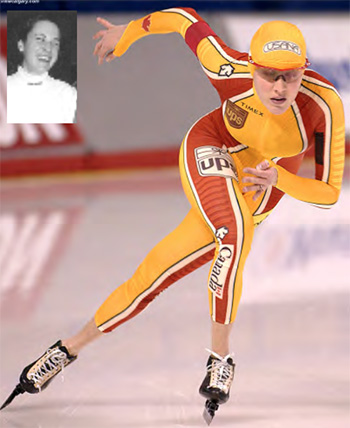

February 19, 1976 –

She was one of the best long track speed skaters Canada ever produced.

She was one of the best long track speed skaters Canada ever produced.

Cindy Overland had all the requisite skills – she was determined, competitive, had plenty of athleticism and endurance, and was serious about her responsibility as an elite athlete.

The only thing missing was luck.

“Cindy was tough!” said former coach Tom Overend. “She trained and skated with aches and pains so frequently, but they never stopped her.”

Overland began skating at age 3 on her dad’s frozen backyard vegetable patch, and joined the Cambridge Speed Skating Club a year later. For the next 23 years, speed skating dominated her life, and she dominated the long track of her peers.

Overland moved to Calgary’s Olympic Oval to train in 1991, at the vanguard of a Cambridge exodus that saw most of the top skaters move west. It was a necessity, as long track ice was limited to a few spots in Canada during the winter months. In Calgary she could train year round.

A 13-year member of the national team (junior and senior), she was seven times a national champion. Yet she was plagued with either illness or injury at key points in her career and largely because of this, was never able to compete as a healthy athlete at the Olympics.

“We always wondered how good she could have become since when she first moved to Calgary, she was a much better skater than Kristina Groves,” said Overend, speaking on behalf of his coaching partner Lisa Gannett. “The injuries and illnesses that Cindy suffered through later in her career really sapped the momentum from her career. Without those and with continued training like Kristina did, who knows how good she could have become.”

In December of 1992, she and her younger brother Kevin, destined one day to become an Olympic medalist, were involved in a bad car accident. Kevin was driving Derrick Campbell’s Eagle Talon when it was hit by another driver. Although the skaters were hurt, they got off relatively lightly given that the car was totalled. Still, the injuries – both physical and mental – were enough to take away any chances they had of qualifying for the 1994 Olympic Games. Both had outside shots, but after the accident, they had no chance.

In December of 1992, she and her younger brother Kevin, destined one day to become an Olympic medalist, were involved in a bad car accident. Kevin was driving Derrick Campbell’s Eagle Talon when it was hit by another driver. Although the skaters were hurt, they got off relatively lightly given that the car was totalled. Still, the injuries – both physical and mental – were enough to take away any chances they had of qualifying for the 1994 Olympic Games. Both had outside shots, but after the accident, they had no chance.

What’s more, great efforts were taken to shield Campbell from the news given that he was in the middle of the short track Olympic trials. She would have to wait four long years for another chance.

“We loved to coach Cindy because she was so coachable,” said Overend, himself a former Olympian, and one of the most respected men in Canadian speed skating circles. “She was always asking what could make her a better skater and being so receptive to technical and tactical advice. And she was such a nice person too, easy to get along with and supportive of her team- mates.”

On the ice, she was accustomed to winning. “She was a tough skater and certainly knew how to look after herself on the ice, in short track, and how to train hard in the summer,” said Overend. “We never had to worry about Cindy not doing her programs. She was quite independent with her training and we could trust that she would follow the program apart from our group sessions.”

When Nagano came around, Overland was ready. In those years she was Canada’s top middle-distance speed skater, a title that Cindy Klassen would one day own. But all did not go according to plan at Nagano. Although she was ranked fourth in the world in the 1500 metres, she never got a chance to compete in that event. Instead, after competing in the 3000 metres and lacking her strength, she ended up bed-ridden for nine days with the flu, an illness that wreaked havoc with many athletes in the athlete’s village that winter.

It was a tragic turn of events for someone who had expected so much more. Despite some encouraging words from her father, who was at the Games to see her skate, the disappointment was difficult to deal with.

“After Nagano, I didn’t allow myself to cry,” she recalls. “I was 22 and I thought that overall, it was an awesome experience. I thought I could take the knowledge and experience into Salt Lake City four years later and use it to my advantage.”

She trained and won more races, including Canadian championships, in the intervening years. But the year before Salt Lake, she came down with mononucleosis. The timing couldn’t have been worse. Still, she was able to recover in time to qualify for her second Olympic Games.

“It was difficult to gauge how strong I’d be at the trials,” said the Canadian all-around champion from 1997-2000. “While I didn’t skate a personal best at the trials, my performance still gave me a lot of confidence.”

But once again, at Salt Lake, she became ill. “When this happened I thought, ‘You have to be kidding me. There’s no way I trained the last 10 years for this. That was extremely difficult to come to terms with. I cried for a long time, for Nagano and Salt Lake, and I took a year off. I needed a huge breather.”

She didn’t step on the ice for over a year. But when she did, in 2004, she knew something wasn’t right. She was at the World Championships in Norway when the medical test results came in. The stress levels in her blood, her cortisol levels, were off the charts.

“I got a call saying the results were not good. You need to come back home right away. It was a done deal. That was it.” She was 27 years old and her career had come to an abrupt end. Once again, she thought it couldn’t be happening.

She had accomplished a lot in her years on the national team. Two Olympics. Seven national championships. Some top results in international competition. But there would be no Olympic medal. She had wanted to accompany her younger sister, short tracker Amanda, to the Torino

Games in 2006, but that dream was never realized.