September 21, 1926 – June 5, 1989

Barry Sullivan loved hockey from an early age and although he retired from the sport at 26, he carved out a successful amateur and professional career.

He came from a hockey family. His father, Harry Sullivan, had some success as a player, having played on a team that was beaten for the Ontario championship. There was, apparently, some old-fashioned chicanery in the series, and the elder Sullivan always maintained that Bill Hewitt, longtime secretary of the Ontario Hockey Association (OHA) and father of Foster Hewitt, the legendary broadcaster, had turned out the lights and put Sullivan’s team at a disadvantage.

Barry Sullivan was born at Lamb’s Nursing Home in Preston, at the corner of Waterloo and William streets. Despite this father’s dislike for Bill Hewitt, young Barry, as a boy, would pretend he was Foster Hewitt calling the play-by-play: “He shoots, he scores!”

He collected Beehive corn syrup pictures of all the NHL players of his time, and was so effusive in his pretend announcing that his sister Paula recalled, “I remember thinking, ‘If you don’t be quiet…’”

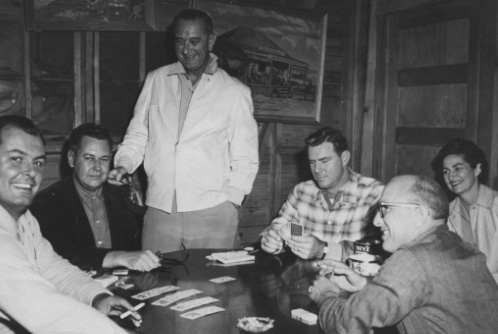

But, as she came to learn, whatever Barry did, he did well. He became an avid boater and fisherman. And he always caught fish. He was a scratch golfer, and once played with PGA starByron Nelson.

As a member of the Preston Scout House Band, he threw himself into the bugle and later, the drums. And if he wasn’t practicing the bugle out on the verandah, he was in the driveway practicing his slapshot, and driving the neighbours nuts.

“He was very competitive,” recalled his sister. By the time he was playing Junior A hockey for the Galt Kist Canadiens, he knew he had come a long way from the days he wore Eaton’s catalogues for shin pads, or delivered newspapers.

He’d also overcome a serious illness. At 10 he was slowed down when he contracted scarlet fever, something his family believes he caught from swimming in the Brewery dam. As he convalesced, his mother and aunt taught him to play bridge. Slowly, but surely, he regained his strength and eventually took to the ice again, playing goalie. As he grew, he developed a rich baritone voice, which comple- mented his charismatic personality and handsome good looks.

Playing on the road for Preston one year, one of the fans was yelling that Sullivan was too big and too good for the league.

“He should be off the ice,” said the fan. “He’s too old.” But Barry’s mother was in the stands nearby and asked: “Are you sure he’s too old?”

“Oh yes,” said the fan. “Well,” said Barry’s mother, “I don’t think so. I was there at the birth.”

Soon, he was playing junior hockey for Preston, then a few games with the Stratford Kroehlers in 1943-44, and the Galt Kist Canadiens.

In 1944-45 he became a standout right winger with the Oshawa Generals, where he scored 21 goals and added 14 assists in 20 games. He turned so many heads that season that he was an add-on to the Porcupine Combines in their drive for the Memorial Cup in March, 1945. Then he turned pro the following season (1945-46) with the Omaha Knights of the USHL along with some future NHLers like Gordie Howe.

The following year he scored 42points for Omaha in 38 games, helping the team win the league championship series in1947, before moving to the Indianapolis Capitols. In 1947-48 he was called up from Indianapolis of the AHL– he scored 22 goals that year — for a single game with the Detroit Red Wings, but for the next several seasons he spent his time in the minors, where he was a consistent goal scorer, topping the 20-goal barrier three more times in the AHL.

His best season was in 1947-48 when he scored 32 goals, and 70 total points, in 63 games.

“Suitcase Sullivan” went to the St. Louis Flyers for three seasons (1948-51) and in 1952 he helped the Providence Reds reach the AHL’s Calder Cup final, scoring 72 points in 61games. He was named to the AHL second all-star team that season.

He had an almost equally banner year in 1952-53 with the Reds, scoring 60 points in 61 games.

It was at that time that the big, strong Preston product hung up his skates and entered the business world with Falstaff Brewery in St. Louis, Providence and Chicago, followed by the Lonestar Brewery in San Antonio.

When he died, he was just 62. “He was a great brother,” said Paula.