September 8, 1982 –

When Nathan (“Nate”) Brannen retired from competitive running, he had won the respect of competitors the world over, having competed in three Olympic Games. And although he carved out a world-class middle-distance running career, when growing up in Preston it was hockey that first captivated him.

He and his friends were all athletic, and like most young kids, enjoyed playing every sport they could. “By Grade 7-8, I got more into hockey,” said Brannen, “and then got a little more serious with running.”

But even as a nine-year-old Brannen took part in the annual Can Amera Games that pitted Cambridge athletes against their counterparts from Saginaw Townships, Michigan. He continued running track in Can-Amera for several years.

“I remember that we were trying to limit the number of events the kids could enter,” said Can-Amera track convenor George Aitkin, “to allow more children into the Games, but Nathan was the best in everything.”

In the 1993 Can-Amera Games, competing in the 9-10 age category, Nathan won the 200m, 400m, 800m, high jump and was on the winning 4X400m relay team. He also finished 4th in the long jump. “We ran out of medals and I remember delivering a couple of golds to his home a week or so after the Games,” Aitkin recalled.

In the mid-1990s Aitken used to pick Brannen up at the bottom of Shantz Hill en route to Tri-City running practice in Waterloo in all weather and seasons.

Brannen never ran the Can-Amera torch relay. “He was too valuable (and young) to risk in the torch run so he never ran it.”

Characteristically, Brannen was very intense as a competitor and was disappointed when he didn’t win a race he thought he should have won.

“Once, around 2000, when a teachers strike interrupted cross-country season, Brannen and the Preston team weren’t allowed to go to one of the big meets (maybe CWOSSA). Nathan went on his own anyway, and won his race. The principal called him into the office the next day and asked him how the other runners had felt being beaten by a runner who wasn’t supposed to be there. I was told his reply was something like – “They would have felt guilty winning a race that he (Nathan) should have won.”

By then it had become apparent that he had more than a little natural talent as a runner. In the 9th grade his coach told him running was the sport in which he could potentially shine.

It was club coach Peter Grinbergs who got him to focus on running, which coincided with the start of his high school career. Still, in Grade 9 at Preston High, Brannen played basketball in addition to cross-country and track, marking the only year he participated in other sports during his high school years.

Grinbergs’ encouragement helped Brannen begin one of the most distinguished athletics careers by any high-schooler in the land.

Each fall he would run cross-country, then do indoor track during the winter, and track in the spring.

“In Grade 9 I did well in Waterloo County,” said Brannen, who that year won the county cross-country championship, as well as four track events (800m, 1500m, 3000m and 4x400m relay), “but at the provincial level I wasn’t as good and ended up finishing 9th in the 1500m and 7th in the 3000 metres.”

For most high-school athletes, making it to OFSAA, let alone finishing in the top 10, would have been enough. But not for Brannen. Instead, it motivated him to get even better for the next year.

“I might be a little bit of a dreamer,” he admitted, “but even at that age, when I wasn’t even close to being the best in Ontario, I thought I could be.”

He was 13 that year and already entertained thoughts of not only winning provincial and national championships, but of making it to the Olympics. Three years earlier, when he was 10, he had wondered to himself, “Do I want to be in the NHL or NFL?” At the time, the NHL won out, but the ensuing years would present a different path.

“I just always had these big goals and aspirations that I believed in.” He had no illusions that anything would come easily, or that things would be handed to him, even if he did become an OFSAA champion. “I didn’t want anything to be given to me. I was willing to go out and train as hard as I could to get it.”

He really started to excel as a runner in Grade 10, when he finished second in the province in cross-country. “From that point on I never lost another race in high school at the provincial level.”

Indeed, he went on to win nine OFSAA gold medals, and was runner-up at the Canadian championships three times.

Retired principal and high school track coach Mark Hunniford, then coaching track at GCI, recalled a maxi meet held at Centennial Stadium in Kitchener during Brannen’s senior year. It was late April. Hunniford had been an OFSAA runner himself during his high school days in London. He knew Brannen was going to run the 400 metres at the meet, which was highly unusual for him as he was known as an 800-metre and 1500-metre specialist. So Hunniford asked Brannen what time he figured he’d run.

“Fifty,” said Brannen, meaning 50 seconds.

“Ian Forde, our top 400-metre runner at GCI, and one of the top 400 metre runners in the province, when he found out Nathan was going to run the 400 at the maxi meet, said, ‘I’m not running.’”

That year Forde finished third in the OFSAA West Regionals 100 metres in 11.24 seconds, and was third in the 200 metres. But his race was the 400m and he was one of the fastest 400 metre runners in Ontario.

Hunniford looked at Forde. It wasn’t like Forde to shy away from a race.

“No way,” said Forde, in no uncertain terms. “One of the only advantages I have is that people think I’m going to win (the 400m),” Forde told Hunniford. “But if I run against Nathan in a race that’s not his, and I don’t win, I have nothing to gain from this. Sorry coach.”

“I didn’t argue with him,” Hunniford recalled.

Hunniford put a watch on Brannen to clock his time. He ran the 400m in 50 flat, which was a full second faster than what Forde would run at the OFSAA West Regionals a month later. And the 400m was not even Brannen’s race.

“And at that moment,” said Hunniford, “I thought, How good is Brannen? How good is he? You see stuff like that and you just wonder. I was in awe.”

Only a few years earlier, Brannen won his first OFSAA medal, though it wasn’t gold. In Grade 10 he got injured and wasn’t able to compete after the cross-country season that fall when he placed second at the OFSAA cross-country meet. It was the last silver medal he would win as a high schooler. But that first OFSAA medal, even if it was silver, was one of his most memorable medals because it proved his dreams were within his grasp.

He would have to wait until Grade 11 for his first provincial gold medal. When that came it seemed to open the floodgates. That year he won three OFSAA golds (cross-country, 800 metres and 1500 metres), a feat he repeated over the next two years.

As he finished up his Grade 12 season, Brannen had established himself as not only one of the top runners in the province, but as one of the top runners in the nation. His final year in high school — Grade 13 — was more about setting records.

His senior year was notable in that he ran at the Senior National Championships (as an 18-year-old) instead of the Junior National Championships, and finished second in the 800m. “That’s what qualified me for the World championships in 2001 as a high-schooler.”

Although he’d made the Pan-Am Games team before that, and had run in a couple of dual meets with the U.S., as well as a World Cross-Country championships, that world senior championships was his first big exposure to international competition.

“That really gave me the belief that I could compete against the world now.”

At those Worlds, in 2001, Brannen was the youngest competitor in the competition in any event. “It was an eye-opener but also gave me the encouragement to want to be better.”

He turned a lot of heads when he broke the Canadian junior record in the 800 metres by nearly a full second, running 1:46.60, which bettered the previous record of 1:47.7. That time would have placed him second at the Canadian senior championships.

But he did more than that as he closed out what was unquestionably one of the greatest high school athletics careers in Canadian history. He also ran a sub-four-minute mile, only the third Canadian high schooler to accomplish the feat, and just the seventh junior (under 20) in North America to do it.

For the record, the first two Canadians to achieve that feat were Brantford’s Kevin Sullivan and Ottawa’s Marc Oleson. Oleson, a good friend of Olympian Doug Consiglio, ran 3:58.8 at the Harry Jerome meet in BC on June 12, 1983.

Brannen ran the historic mile in Halifax, Nova Scotia, at the Aileen Meagher Track Classic. Meagher, a Halifax native, participated in the 1936 Berlin Olympics, on the same Canadian team as Preston runner Scotty Rankine. Meagher won bronze in the 4x400m relay at those Games.

Now, leading up to that mile race in Halifax, Brannen had been running really well and Grinbergs knew the meet director in Halifax. The mile distance is not typically run in Canada, but breaking four minutes was, and still is, a big deal in the U.S. and worldwide.

“There were probably only 100 people in the stands for the mile run,” said Brannen. “I ended up running 3:59.85.” For such a notable achievement, few ever saw it. “It’s much different now. If you break four minutes for the mile in high school, you’re signing a professional contract and your name would be all over the internet.”

As he closed out his high school career in 2001 Brannen was ranked fifth in the world among juniors over 800 metres, and 10th in the world over 1500 metres.

Being around Cambridge runner George Aitkin, he had heard about some of the legendary local runners of the past, like Rankine, Ab Morton, Cliff Bricker and Billy Reynolds, as well as contemporary runners like Doug Consiglio and Carmen Douma.

“This area was a hotbed for runners, and when you add in Kitchener, and places like Brampton with Graham Hood, it was a good time to be a runner in Ontario because of all those names that came before you. Ontario has always produced great middle distance runners. Luckily I was in that stream, and was able to watch those guys and get encouragement to keep with it.”

During his sub-four-minute mile Brannen kept up a torrid pace, but during the last lap, he knew he had to dig pretty deep if he was going to do it. “I didn’t know until a couple of minutes after the race that I had broken the mark.”

The clock, as he crossed, appeared to show 3:59, but the person who starts the clock isn’t the official timer.

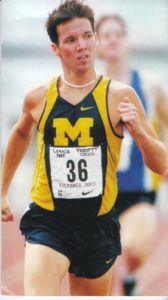

For the next several years Brannen’s focus was on both the 800 metres and the 1500 metres, but the 800 became his speciality during the next four years at the University of Michigan.

Brannen chose the University of Michigan for a number of reasons. Academically, the school was highly regarded, and athletically, a number of outstanding runners had run for Michigan coach Ron Warhurst, including Kevin Sullivan.

“I felt very comfortable with the team there, but most importantly, with the coach. We just connected really well, and they always had a huge contingent of Canadian runners going there. Kevin Sullivan went there. You look at almost any of the top 1500 high school runners in Ontario, and they either went to Arkansas or Michigan. I just felt more comfortable at Michigan.”

The legendary Sullivan was still at Michigan when Brannen arrived. Sullivan was serving as a volunteer assistant coach. “I spent my first year there with him. We trained together, and indeed, throughout my career, I’ve trained with him a ton of times. I moved to Tallahassee for a while when he was there, and there would be national team trips where we’d train together and we were both coached by Ron for a good portion of our careers.”

“Growing up I looked up to Kevin as a runner that I wanted to be like. He had so much success and was known by everyone in Canada. He’s just a standup guy and a super-talented runner.”

Brannen used Sullivan as his yardstick, figuring if he became as good as him, he would have had a successful career.

“I think I got pretty close to him, and although I didn’t break a few of his records, I still have some Canadian records of my own, but growing up, I looked up to him. I always thought if you could be as good a runner as Sullivan, then you’d be a damn good runner.”

But despite his favourable initial impressions of Michigan that enticed him to Ann Arbor, during his first term he had second thoughts.

Brannen struggled with cross-country during that freshman season. After competing at the World Junior Championships in Edmonton that August, where he was focussed on the 800 metres, he went straight into cross-country camp at Michigan.

His mileage bumped up a lot, and he wasn’t ready for it. It was a struggle. “I wasn’t quite sure after cross-country season, when I went home at Christmas, if that was the place I wanted to be. For me, it was more of an internal struggle. I was so good at what I did in high school, and so to be at Michigan and not running as well as I should have, I was thinking clearly the program wasn’t working for me.”

He returned home for Christmas and talked with Pete Grinbergs. Grinbergs told him to stay and finish out the year. “See how it goes.”

Brannen returned to Ann Arbor with a different attitude and he ended up making indoor nationals that year, qualifying in three events. His best finish as a freshman was fifth at the nationals.

“Things turned around and from that point on I ran really well, and I’m glad I stayed because I had some of the best years of my life there.”

But he also met another freshman that year at Michigan, a female named Theresa who would become his wife. That developing relationship helped immeasurably as well.

Today he savours the time he spent in Ann Arbor. “University of Michigan is an amazing school. It was great there. I was lucky enough to graduate with a degree from such an incredible university. There was a ton of talent on the team at the time, including Nick Willis and another Canadian, and Andrew Ellerton. Mike Woods arrived in my senior year. It was a lot of fun. Every race we went to, especially if we were running a distance medley relay, we knew we were going to win. It wasn’t a question of whether we were going to win; it was whether we were going to break the NCAA record that weekend, and/or the Big 10 record.”

In his sophomore year he won his first national championship as a Michigan Wolverine, winning the 800 metres at the indoor nationals. Going into the race he thought he could do well, but he didn’t think he would win it. “Pulling off the win as a true sophomore — I was pretty young — was the first really big win I’d had in my career to that point and that’s the one I always remember.”

When people ask about the biggest thing he ever did in his career, he usually mentions the Olympics, “but the thing I always remember is winning the NCAA’s for the very first time.”

After that he went on to win four NCAA titles, and was an 11-time All-American (three in cross-country and eight on the track). He also broke two world records while there as part of a relay team.

He broke the NCAA mile record in his senior year, running 3:55.11 — this is also the Canadian indoor record — and set a relay record. Brannen owns the Canadian indoor mile mark of 3:54.32, set as a professional a few years later (2014) during the famed New York Road Runners Millrose Games in New York.

Brannen had hoped to make it to the 2004 Olympics, but an injury forced him to wait until 2008. He had badly sprained his ankle during a distance run, and initially the X-rays indicated it was broken. Fortunately, it wasn’t. As it was, he missed about six weeks in the key period leading up to the Games. He attended the Trials — he was fourth — but he just couldn’t get back up to speed in time to qualify.

Waiting four long years was the price he had to pay. As every athlete knows, four years for a runner is almost a lifetime, during which anything can happen. On November 30, 2007, Brannen underwent back surgery.

For two months he didn’t run. It was February before he could start to train again. “It was a long, slow process going from zero running to slowly getting back doing just three to four minutes of running a day until finally qualifying in July for the Olympics.”

There were a lot of ups and down during those months, including many races he entered to try to get his Olympic qualifying time. He qualified, finally, at a race in Italy.

He had run at the Canadian Olympic trials on a Sunday and finished second, but still hadn’t run the necessary qualifying standard. What’s more, time was running out. He returned home Monday, then boarded a plane bound for Rome on Tuesday, and ran the standard on Friday in Italy.

Then he started training for his first Olympics.

The back surgery affected qualifying more than it did his performance in the Games. The qualifiers require athletes to be at their peak just to qualify and because they are held early, Brannen didn’t have enough training to get him through. “When I got to the Olympics in China, I was ready to go and felt 100 per cent.”

But unfortunately, the nerves of being in his first Olympics got to him. “The first round I ran great,” he said. “I got second in my heat and qualified easily for the semi, and then I didn’t sleep from the first round to the second round, just being too excited. It was too hot in the Village — they had these sheer curtains that let in all the light and I couldn’t sleep; I was stressing about not sleeping. I struggled in the semi final and missed the final by three positions. That was tough.”

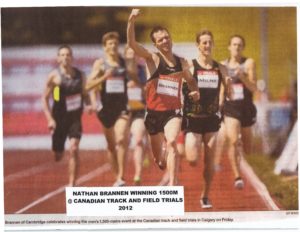

It would be another four long years before he had a chance to redeem himself. Yet he resolved to be at his peak for the 2012 Games. “Looking back at my career, that was the fittest I’ve ever been. I went into the Olympic trials and was super confident. I won the trials pretty easily.”

At the trials he and Taylor Milne were battling for first with 100 metres to go when Brannen put it into another gear. They had been side-by-side, but Brannen was able to kick away from him. After the race Milne, who finished second, said to Brannen: “I’ve never seen you this fit.”

As the 2012 Olympics approached, Brannen was at the top of his game. “I’ve never had that much clean training where I didn’t miss any time — no injuries. I’ve had a lot of stress fractures, back injuries and stuff like that, but in 2012, I’d had a really nice buildup and was able to really focus on training without significant ups and downs. I think going into the Olympics I won 11 of 12 races and was one of the most consistent runners that year. Looking back that fall, I counted how many times I’d broken 3:30, the qualifier, something like 17 times, which was an unheard of number of times.”

Then came his second Olympics, and things were different. “I was thinking this was my time when to make the final and be top five, but never thinking a medal was out of the equation, though knowing I would need everything to line up on that day to get a medal.” If he made it to the final, he felt he had a chance.

“(A medal) would have meant some of the top guys would have to run bad, and me running the race of my life, but in the back of my mind I thought I could be top five and maybe sneak in for a third.” If ever he had all the stars in alignment to run the race of his life, it was that summer.

Brannen qualified for the semis in London, and things were looking good. But many Canadians remember what happened with just over a lap to go in that semi-final. Brannen and another runner tangled legs, and Brannen fell to the track.

He was interviewed by CTV following that bitter disappointment. “I watched (American) Leo Manzano get second and I thought, good for him, but that was the race — that would have been the race to snag a medal. It was bitter sweet.”

In truth, it was devastating. “It was tough. I’m still not over it to this day. Falling at such a big event, I’ll never get over it completely.”

It did, however, provide encouragement to go on and pursue a third Olympic berth. It made him realize how much he loved the sport and how much he wanted to come back, even if it did take four more years.

“That’s what kept me going through 2016.”

People would offer encouragement, telling him, “You’re going to be even fitter in 2016,” but in his mind he knew they didn’t truly understand that he was at his peak in 2012, and that it’s hard to have everything come together like that. In the back of his mind he kept thinking, ‘An athlete gets only one of these years in a career, and that was probably my year.”

Still, that knowledge didn’t discourage him from trying to return to the Olympics. And return he did, to not only make the finals but finish 10th.

“Four years is a long time,” he said. “So much can happen. I had two kids by then, so it was hard to envision what was going to happen in four years. I could train perfect for three-and-a-half years and then get injured and it would all be, in my mind, a waste of time.”

If he had periodic doubts, he also had an inner voice that told him it was worth it. “This is what I want to do.”

The year after London he made the finals at the Worlds. That was the first redemption. It proved he should have been in the final in 2012. But from 2013 through 2016 there were several disappointments.

He and his coach decided to focus on less racing and more training. He didn’t even try to make the Commonwealth team in 2014. “I was having a bit of an achilles issue so we shut down the season, not wanting to make it worse or tear anything.”

But the following year, even though he’d had some success, including a silver medal at the Pan-Am Games in Toronto, he wasn’t selected for the Canadian team going to the Worlds. He had run the fastest time in Canada, by two seconds that year, and he’d won Nationals, but they chose somebody else over him.

“It was a tough year,” he admitted. While his competitors were all racing into September, Brannen and his coach shut things down early and started the buildup for Rio a little sooner than normal.

The way those two years unfolded, even though they were tinged with disappointment, probably played a pivotal role in ensuring Brannen had a successful run-up to the 2016 Olympics in Rio.

But at the time, he couldn’t have known that. In 2015 Brannen had what he described as his worst buildup ever for a summer track season. Compounding things, it was the prelude to an Olympic year.

“I spent a lot of time here in Ohio and the weather was awful. I struggled in workouts, and I wasn’t hitting times that I was easily hitting in previous years. I was very discouraged. And then, my first race I opened up in, I ran 3:36.” This was two or three seconds faster than what he had hoped for. Maybe things weren’t as bad as he felt.

Mentally it was a trying year. But Brannen had lived through a great deal of adversity throughout his long career. “What I failed to realize was that I did all the training by myself and it was close to zero weather in wind. It was freezing out and windy and I was thinking I should be hitting the same times as previous years being in Arizona when it was hot.”

He hadn’t factored in the weather, the wind. All he could see was that he was missing his times. It was hard for him to see the big picture given that he was doing it all himself.

Brannen had good support, and good backing, to keep his dream alive, to keep going. But he had seen many talented runners through the years who couldn’t go on, and made the decision to move on and get jobs.

“It’s hard to support yourself as an athlete. You see it way too often that guys don’t realize their potential because there just isn’t enough funding or motivation — whatever it is — or they have put so much into it and missed the mark. They decide they can’t try again for another four years as they’ve put everything they had into the last four years. Olympic sports are tough sports to be part of.”

Brannen graduated from Michigan and the highly competitive NCAA in 2005, so when he took to the track for this third Olympics, in Rio, he had been out of university, and the NCAA, for 11 years. Yet he was still going strong. By the time he hung up his track shoes in 2018 he had run almost 13 years as a professional. During that time the lowest he was ever ranked was 20th in the world.

By then, he was contemplating retirement. He knew it was around the corner as he traveled to Rio for his third Games. But he didn’t think of retirement. He had weightier things on his mind for Rio.

He approached his third Olympic Games with a much different approach than his two previous Olympics.

“I didn’t know what was going to happen,” he said. “I knew I was pretty fit. Just before the first round in Rio, my coach asked me how I felt. I said I felt good. He asked me how I thought the race was going to go. I told him I was either going to make the semi or I’m not. He said that was a good attitude because I didn’t have a lot of pressure on me.”

The athletes village was more like apartments, and this time he had a dark curtain that kept the light out. He was not about to be distracted from the task at hand.

“I literally had a suite all to myself, until a couple other athletes arrived. I had air conditioning, the curtains got completely black-out dark, so it was a much different experience. I was like a hermit, just staying in my room. I went to the track to train. I went to the dining hall to eat, but other than that, I had a Netflix account and just watched TV and got ready. Because I’d been to the Olympics two times before, I didn’t feel the need to do any sightseeing. I didn’t go to any other events to watch anything. I just focused on my stuff, and because I was much older, I felt like I was there to make the final and that I was going to do what I needed to do to make it. I think that attitude helped me take a lot of the stress off. I knew I was fit. It was either going to work out, or it was not. There was not much I could change about it at that point.”

One thing Brannen didn’t participate in at Rio was the opening ceremony. “I’ve never done an opening ceremony at the Olympics,” he said. “I’ve done the closing, but not the opening.” Track events start late in the Olympic calendar and he was never there in the village for the opening.

It’s a minor regret, looking back now, but he doesn’t think he would have changed it. “I never wanted to risk the chance I had of doing better in my event at the Olympics.”

It all worked to his favour. Brannen reached the semis and then advanced to the finals. The final was a race of positioning, not speed, and unfortunately, Brannen didn’t position himself very well, something that only became apparent after the race was run.

Still, getting to an Olympic final was a milestone in a career full of highlights. As a Grade 9 runner at PHS, he had made it to OFSAA, but had not been content to be a finalist. That same kid, as a grownup, was not simply content to be an Olympian. He knew he had more. He sought to be an Olympic finalist.

“It was a big weight lifted off my shoulders,” he would later admit. A long-held goal finally realized. “It was so stressful those four preceding years after going down in 2012. I didn’t sleep well for months after 2012 — every time I thought about it I would break down — so it was a huge relief that I made it, and at the same time, I could tell myself that yes, I am one of the top 1500-metre runners in the world, and I just proved it at almost 34 years old, which is really not an ideal age for a middle distance runner.”

Where once he had been the youngest in his first World Championships, Brannen was now the oldest runner in the final. “It would have been nice if I had been 29 and in the final at London as I would have been a much different runner, but it was getting close to the end of my career, and it was nice to end like that, knowing I was, and am, one of the top middle distance runners in history.”

Making the finals had given him a bit of the fire he had grown accustomed to in his early years. It had rejuvenated him. He was not quite ready to retire.

Indeed, making the final brought a bit of excitement back to his love for running, a love that never waned. The years had presented so many ups and downs, and in their entirety, they took a toll.

“I probably had at least a significant injury every single year leading up to 2016. And each time I’d think, I can’t do this any more. It’s so hard to mentally go through an injury, build back up, and honestly, I probably ‘quit’ the sport four or five times through the years between 2012 and 2016. But I would quit for about a day, and then I’d get a little green light that I’m healing faster, or I’m good.”

Brannen didn’t have a lot of funding for 2017, but he wanted to continue at least another year. “I didn’t like the idea of ending just because I’d made the Olympic final and I had done what I wanted to do. I wanted to go one more year and have fun with it, training for 5K, and I wanted to run a fast 5K.” Unfortunately he trained a little too hard that post-Olympic year and burned himself out.

But it was hard to check the competitiveness that took him to three Olympics. As he approached his 35th birthday, he ran his fastest ever 3000 metres indoors in 2017. It was about a second faster than he’d ever run it before. But slowly, after 2017, he began to wind things down. He retired right after Christmas in 2017.

“For 13 years — ‘you can ask my wife Theresa’ — I lived, breathed and ate running,” he said. “Everything I did was geared around running. In the off-season I would maybe have a little bit of fun, but I truly enjoyed (running) and that’s why I still run to this day. I enjoyed going to the track and doing a workout that I knew on that day, maybe a handful of people in the world could have done with me. That was motivation in itself. Just being on the track, on my back, and not being able to get up because I knew I just did something runners dream of doing.”

He still runs, but he doesn’t race competitively now. He continues to put in the miles, but as he explains it, if he gets up one day and doesn’t want to run, he doesn’t have to. More importantly, he’s not on the road and away from his family now.

For Brannen, the stress of being a world-class athlete — “always go, go, go” — has been replaced with a more ordinary existence. “Now, I can just be a normal person.”

At the time of his retirement Brannen held four Canadian track and field records; in the indoor and outdoor 1000 metres (2:16.86 indoor, 2:16.52 outdoor), 2000 metres (4:59.56), and the indoor one mile (3:54.32).

Brannen has won the city of Cambridge Tim Turow athlete of the year award several times and is one of the most decorated distance runners in Canadian history.

“Honestly,” he says, “I think I could make one more Olympics.” In fact, his fitness and training, which he insists is just for fun, has not gone unnoticed by his wife.

“You’re going to go for 2020, aren’t you,” she would ask in the winter of 2020.

“No, no, no,” said Brannen. And then he’d get back to the track for a workout.

“You’re training for it, aren’t you?”

“No, trust me, I’m not,” he reassured her, over and over.

“So I made a deal that I wasn’t, and that I was good.” But in his mind, the idea of switching to the 5K for another shot at the Olympics, was within the realm of possibility.

But in March of 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the 2020 Olympics and everything else in its wake, Brannen was glad he made that deal. On the very day the IOC announced that the Tokyo Olympics would be postponed for a year, he was glad he had not committed to another Olympics.

“There’s no way I could go ’til 2021.”

If he had committed to Tokyo, he would have been all in. During his competitive years, he always tried to push his training regimen, to get as close to what he called the “Red Line” as he could.

“You want to be as close to that red line as possible,” he explained. “Going beyond the line is more about the risk of injuring yourself rather than burning out. If you can stay as close to your ceiling with the red line as possible, without getting injured, that’s when I felt I was unstoppable.”

At that point he was mentally on top of his game, supremely fit, and knew he was going to be hard to beat. “That’s what you strive for. You strive to be right under that red line. If you think of what your breaking point is, you back off slightly and that’s how I approached my career.”

Given the postponement of the Games, he saved himself one final disappointment.

He is content, mostly, with his running career, save for that one mishap in London. He can now look back on the entirety of his running life, from those early days with Aitken in Cambridge, to the days of Peter Grinbergs, and of his gloried career at PHS with good friends Scott Thorman and Allan Lemieux, and PHS coaches like Bill Horwitch.

Sometimes he thinks back to his first Olympics, when he was part of an Olympic team that included Thorman. Imagine, two kids from PHS, at the biggest sporting event in the world.

“Our first Olympics we were together, in 2008,” said Brannen. “I almost made 2004 but got injured, so when they reinstated baseball for 2008 and I made the team, it was pretty unique and so much fun that Scott and I both experienced it together. We went to the Great Wall after we had finished competing in Beijing.”

To this day he, Thorman and Lemieux remain close. “We’ve all gone separate ways, but at Christmas when we’re all back in Preston we see each other and it’s as if it was yesterday. It’s so nice to have such close friends.”

Brannen lives with his wife Theresa of nearly 10 years and their two children, Gianna (8), and Grayson (5), in Avon Lake, Ohio, just 20 minutes from Cleveland. “She supported me through all these years,” he said. He’s also had an opportunity to coach.

What made Brannen a remarkable athlete was not just his ability as a runner, which was immense, but his desire to be the best, to strive to be an Olympian, and the hunger to make it to the finals. His longevity as a world-class middle-distance runner, through three Olympics — and almost four — is partly due to that innate ability, which his early coaches first saw, but it is also due to the hard work he has put in along the way. Few could have worked any harder, and for more years, than Brannen. He was near that red line far longer than most.

Yes, there were some bitter disappointments along the way. Some so devastating that others might have called it quits. But Brannen always knew there was one thing he could count on, that he could retrieve from somewhere deep within him, and that was his capacity to work hard. He was never afraid to work hard. In fact, he embraced it.

Remember how, when finishing a workout, having reached for that red line, he found himself collapsing on the track afterwards, exhausted, and he would think of the hard work that put him prone onto the track, gasping for air?

To others, looking at him so winded and on the ground, they would never know the inspiration that was even then comforting Brannen. There was Brannen, spent and down on the ground looking for all the world like the sport was perhaps too much for the man, that it had taken too great a toll.

But nothing was further from the truth. It was precisely at times like these that Brannen took comfort in knowing that what he had just done, the workout he had just endured, was something that perhaps only a handful of other humans could ever know.

God, how he loved striving; how he loved running.